Back in the early days of the Great Recession, the LA Times ran a story called Can a troubled economy actually improve public health?

Back in the early days of the Great Recession, the LA Times ran a story called Can a troubled economy actually improve public health?

[S]trange as it may seem, bad times can also be good for health. Forget individual health for a minute. This is about the macro picture, the health of entire societies. And there statistics show that as economics worsen, traffic accidents go down, as do industrial accidents, obesity, alcohol consumption and smoking. Population-wide, even deaths from heart disease go down during recessions.

The report was based on the work of economist Christopher J. Ruhm – the favorite expert of journalists who want to attract readers with something counter-intuitive.

Two years later, no one is so glib. Yes, we did manage to pass health care reform. More people will eventually have health insurance, but that’s not until 2014. In the meantime, people are not just unemployed. They’ve been unemployed for a long time. And those people need to eat.

Why isn’t unemployment recovering?

I just read a two-part series by Paul Krugman and Robin Wells, “The Slump Goes On: Why?” and “The Way Out of the Slump.” Krugman has written before about an idea called the paradox of thrift. If everyone – not just individuals, but corporate employers – cuts back on spending and saves (pays down their debt), the economy slumps and can’t recover. This is related to the fallacy of composition. Logically, what’s true of the parts must be true of the whole. It’s a fallacy because saving — normally a good thing for the individual parts — ends up being bad for society as a whole.

Economic theories are engaging in the abstract, but human behavior doesn’t always conform to logic. It continues to resist capture by the dismal science of economics. I was reassured – though not comforted — to see Krugman and Wells acknowledge limitations — or at least temporary failure:

[I]t’s hard to read current writing about the economic crisis without a sense of despair: economists don’t even seem interested in solving the problem of continuing mass unemployment.

Unemployment, technology, and the global economy

To understand the intractable nature of mass unemployment, I prefer the perspective of a historian. In Ill Fares the Land, Tony Judt discusses the consequences of technological advancement for society.

Since the industrial revolution, technological change has put people out of work. The same amount of work can be done by fewer people. Skills become obsolete and redundant.

Our economic system keeps expanding, however, creating new forms of employment. If we end up working at McDonald’s, we may not be paid as well as before, and we may not like our new jobs, but technically we’re not unemployed.

Most people in Western developed countries — including our immigrant parents and grandparents — would say they’ve experienced a rising standard of living for over a hundred years – the period from 1870 to 1970. Education was free. The population became literate. We acquired new skills. Incomes went up.

The advent of a global economy changed all that. Employment now flows to countries that offer cheap labor – countries like China. This has not been good for American workers. And it’s not good for the Chinese worker. I’ll repeat something I quoted before when writing about the rash of suicides at Foxconn, a low-wage Chinese factory that manufactures hi-tech products for western companies.

There is a great injustice at the heart of the whole process of exploiting cheap labor to make the must-have googaws for the world’s affluent. Every suicide at a Chinese factory is an exclamation point at the end of that last sentence. Both the Chinese and international media know this, and so do Apple and HP and Dell and Foxconn’s top CEO, Terry Gou. It just doesn’t look good when your employees start jumping out of windows in steadily increasing numbers. It is a sign that something is very, very wrong in how humans are organizing themselves on this planet. We don’t want to think about it when we’re playing with our smart phones, or reading the new Wired app on our iPads, but it’s the truth, and it bears constant investigation. [emphasis added]

The knowledge industry to the rescue. Not.

To return to Judt’s argument, the only thing highly developed countries can do in the face of cheap foreign labor is to play their ace card. These countries excel with industries that are knowledge intensive: “capital-intensive advanced industries where knowledge counts for everything.” But we are unable to teach the skills those jobs require rapidly enough to keep our citizens employed. The initial learning curve is steep and knowledge intensive skills constantly go out of date.

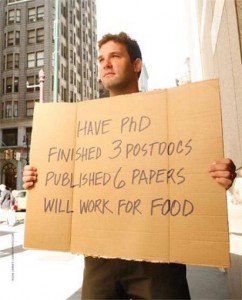

Mass unemployment – once regarded as a pathology of badly managed economies – is beginning to look like an endemic characteristic of advanced societies. At best, we can hope for ‘under-employment’ – where men and women work part-time; accept jobs far below their skill level; or else undertake unskilled work of the sort traditionally assigned to immigrants and the young.

Judt goes on to speculate on the risks to “civic and political stability” posed by those who are chronically left out – “superfluous to the economic life of their society.”

The welfare state is over. There’s an ugly strain of thought afoot that views the unemployed as responsible for their own adversity. It’s the same strain of thought that blames the poor — when they suffer from ill health — for not taking “personal responsibility.” Economists don’t seem interested in solving the problem. Politicians blame the victims. It’s the tragedy of our times.

Ill fares the land, to hastening ills a prey,

Where wealth accumulates, and men decay.

A new Tony Judt book

On a less somber note, I was pleased to learn that Ill Fares the Land will not be Judt’s last book. A few weeks before his death in August, he completed Thinking the Twentieth Century, with Timothy Snyder. You can read more about it here.

Update 10/6/10:

The costs of rising economic inequality (The Washington Post)

Great editorial today by Steven Pearlstein.

In trying to figuring out who or what is responsible for rising inequality, there are lots of suspects. Globalization is certainly one, in the form of increased flows of people, goods and capital across borders. So is technological change, which has skewed the demand for labor in favor of workers with higher education without a corresponding increase in the supply of such workers. There are a number of other culprits that come under the heading of what economists call “institutional” changes – the decline of unions, industry deregulation and the increased power of financial markets over corporate behavior. Over time, more industries have developed the kind of superstar pay structures that were long associated with Hollywood and professional sports.

And then there is my favorite culprit: changing social norms around the issue of how much inequality is socially acceptable. …

There are moral and political reasons for caring about this dramatic skewing of income, which in the real world leads to a similar skewing of opportunity, social standing and political power. But there is also an important economic reason: Too much inequality, just like too little, appears to reduce global competitiveness and long-term growth, at least in developed countries like ours. …

The biggest problem with runaway inequality, however, is that it undermines the unity of purpose necessary for any firm, or any nation, to thrive. People don’t work hard, take risks and make sacrifices if they think the rewards will all flow to others. Conservative Republicans use this argument all the time in trying to justify lower tax rates for wealthy earners and investors, but they chose to ignore it when it comes to the incomes of everyone else. …

Just as income inequality has eroded any sense that we are all in this together, it has also eroded the political consensus necessary for effective government. There can be no better proof of that proposition than the current election cycle, in which the last of the moderates are being driven from the political process and the most likely prospect is for years of ideological warfare and political gridlock. …

Without a sense of shared prosperity, there can be no prosperity. And given the realities of global capitalism, with its booms and busts and winner-take-all dynamic, that will require more government involvement in the economy, not less. [emphasis added]

Update 10/18/10:

Income Inequality: Too Big to Ignore (The New York Times)

Increasing income disparity impacts all of society. (emphasis added)

Recent research on psychological well-being has taught us that beyond a certain point, across-the-board spending increases often do little more than raise the bar for what is considered enough. …

The rich have been spending more simply because they have so much extra money. Their spending shifts the frame of reference that shapes the demands of those just below them, who travel in overlapping social circles. So this second group, too, spends more, which shifts the frame of reference for the group just below it, and so on, all the way down the income ladder. These cascades have made it substantially more expensive for middle-class families to achieve basic financial goals. …

The middle-class squeeze has also reduced voters’ willingness to support even basic public services. Rich and poor alike endure crumbling roads, weak bridges, an unreliable rail system, and cargo containers that enter our ports without scrutiny. And many Americans live in the shadow of poorly maintained dams that could collapse at any moment. …

And in our winner-take-all economy, one effect of the growing inequality has been to lure our most talented graduates to the largely unproductive chase for financial bonanzas on Wall Street. …

No one dares to argue that rising inequality is required in the name of fairness. So maybe we should just agree that it’s a bad thing — and try to do something about it.

Related posts:

The economy, stress, and health

An upside to the downturn?

“Screw You Yahoo”

Suicide in Japan (part 1): The recession

Links of interest: Suicide

A generation obsessed with material wealth

Tony Judt: On the edge of a terrifying world

Resources:

Image source: 12 News

Susan Brink, Can a troubled economy actually improve public health?, The Los Angeles Times, August 25, 2008

Paul Krugman, The paradox of thrift — for real, The New York Times, July 7, 2009

Paul Krugman and Robin Wells, The Slump Goes On: Why?, The New York Review of Books, September 30, 2010

Paul Krugman and Robin Wells, The Way Out of the Slump, The New York Review of Books, October 14, 2010

Tony Judt, Ill Fares the Land

Timothy Snyder, On Tony Judt, The New York Review of Books, October 14, 2010

I have read several different places that unemployment will remain high for several years or more. 10% unemployment may be the new norm. God help us.

Hi Roberta – I know. I’ve heard that too.

I had another thought on this topic, but didn’t want to make the post longer. In the mid-1970s, when I started teaching history of science, I was asked to come up with a class for the Contemporary Civilization department. So I created a course called Life in the 21st Century. (It seemed far away then.) Alvin Toffler had written Future Shock and there were many “futurists” speculating on how wonderful (or terrible, but mostly wonderful) life would be in 30 to 40 years. Genetics was just coming into view, it was a totally pre-digital time (at the personal level), and communicating with a hand-held device was something only Dick Tracy could do.

One of the main issues futurists worried about in the seventies was what people would do with an excess of leisure time once automation and technology reduced the need for labor. How differently the world has turned out.